Discovering better ways of planning and delivering value in engineering teams

[Keywords: Effective Planning, Value Stream, User Story, Story Slice, Engineering Productivity, Business Requirements]

One of the many problems I’ve observed with how teams adopt SCRUM (or any iterative/incremental development model) is the manner in which a.) planning work, and b.) delivering value is conducted. Teams will generally showcase work status on boards with many swimlanes, a stream of stories moving downstream following the rules of a particular workflow. Planning work generally entails user stories coming in from the business (along with UI/UX mockups and acceptance criteria), and dev teams breaking them down into technical tasks (ideally after drawing up preliminary technical designs) before starting actual development.

When the time comes for a sprint/iteration demo, developers wonder why a lot of things they committed to could not be completed, why features and functionality did not work as expected during the demo, why there is so much rework after the demo (apart from changes cropping up due to user feedback during the demo), and why the heck they don’t have enough time to plan work for the next iteration.

Some key factors that give rise to these symptoms are managers expecting developers to estimate stories and provide a fixed ETA, ineffective planning methods, developers lacking minimal up-front technical designs, skipping due diligence activities that could mitigate technical risk, pressure from the top to rush solutions by taking shortcuts, and remnants of waterfall era mandates of ‘tracking everything you do under an issue/ticket’ (even if it’s a 5 minute fix - it will get dragged to become a two day hiatus with emails, ticket creation, and other wasted ceremonies that provide no value). What I would like to address in this post is how developers plan their work (i.e. break down work into granular tasks) when they get user stories from the business.

During my past tenure at :Different as an engineering team lead, we tweaked some changes in the way engineers plan and breakdown work (given a business roadmap), with profound results. Spearheaded by the engineering leadership of the organization and coupled with buy-in from the engineers, the changes in how work was planned and value delivered, created a new way of looking at delivery expectations, both from an engineering as well as business perspective. It also resulted in better engineering productivity, a reduced bug/failure rate, faster cycle times, users being able to see and test incremental value funneled through the delivery pipeline at a regular cadence, and time-boxed iterative planning activities that did not exhaust the engineering team.

These learnings and takeaways are something that I actively advocate, apply, and continuously improve, within the teams that I work with today. For the past few months at Corzent, the team I work with conducted some interesting experiments, and radically optimized the way the engineering team planned and broke down business expectations, and delivered value to end users.

In the beginning, business requirements/stories were broken down into tasks (in a Kanban workflow), that would be flagged as ‘UI’ tasks, ‘API’ tasks, or ‘Integration’ tasks, and so on. Almost all assignable work items would be horizontal slices of functionality (labelled under the horizontal hierarchy it falls into - UI/API/DB) or an integration/configuration/miscellaneous technical task. The first step we took was to do away with the horizontal slicing of stories into UI/API/Integration/DB tasks, and start breaking down user stories into thin vertical cross sections of end-to-end functionality.

To show how this works, here’s an example of a (highly oversimplified) requirement from the business: “As a user, I want to fill in the application details and save them in the system”

The developers, when planning work, could potentially break this story down into the following three story slices:

- As a user, when I click the save application button in main view, I should see a modal popup to enter the application details

- As a user, when I enter the details into the applications detail modal, the entered values should be validated

- As a user, when I enter valid application details in the modal and click on save, the application should be saved successfully in the system

The above three story slices are extracted from the original story. What should be observed and emphasized is that:

- Each story slice can be implemented by a developer and independently deployed

- The first two stories slices do not implement the save functionality. Clicking the save button might display a ‘work in progress’ or ‘under construction’ message/toast

- The scope of each story slice is added in the description/acceptance-criteria, so that anyone testing understands what needs to be verified when testing the specific story slice

- The cycle time of each story slice is between half to one day - anything larger is further sliced

- Story slices are not technical sub-tasks of a user story - they do not mention any technical work nor give any indication of what part of the system will be touched (i.e. UI/API/DB). The story slice showcases only the value statement to the end user

- Implementing a story slice could result in one or more pull requests, which are linked to the same story slice. The PRs could be for a front end UI client, back end API service, configurations, integration, DB, whatever - anything that needs to get the story slice up and running, and ready to be deployed

- If incremental work-in-progress mapped to story slices should not be visible in production until the feature set is complete, they can be implemented behind a feature flag, which can be toggled on for developer and test deployment environments

A developer would then take a story slice into the Kanban workflow, implement it, raise pull requests for review, and merge + deploy the changes, all within the span of roughly half a day to one day.

Observable outcomes:

- Faster cycle time - implementing small units of value imply small PRs, which in turn makes the review/merge/deploy/feedback loop run faster

- Improved developer productivity and agility - the depth of the problem domain + technical solution of a story slice is far smaller and digestible than a complex business expectation compressed within a single user story

- Users/quality-engineers see changes delivered sooner and at a regular cadence, giving them the ability to provide feedback faster, even if the feature is working partially - this reduces rework stemming from bulk changes

- The business gains predictable insight into the ETA of features and feature-sets, based on monitoring the regular cadence of value being delivered and observed downstream

There were some caveats that we encountered and learned from, two of the more important being:

- User stories (and hence story slices) can evolve with time. A user story is not a fixed business expectation set in stone, and therefore should be treated as such. A key point that the team discovered was to get into story slicing only after the business problem is clearly understood + clarified with users, any foreseeable system/architectural constraints related to the requirement are addressed, and space for the possibility of the story evolving with time is provided/accepted by engineers and the business.

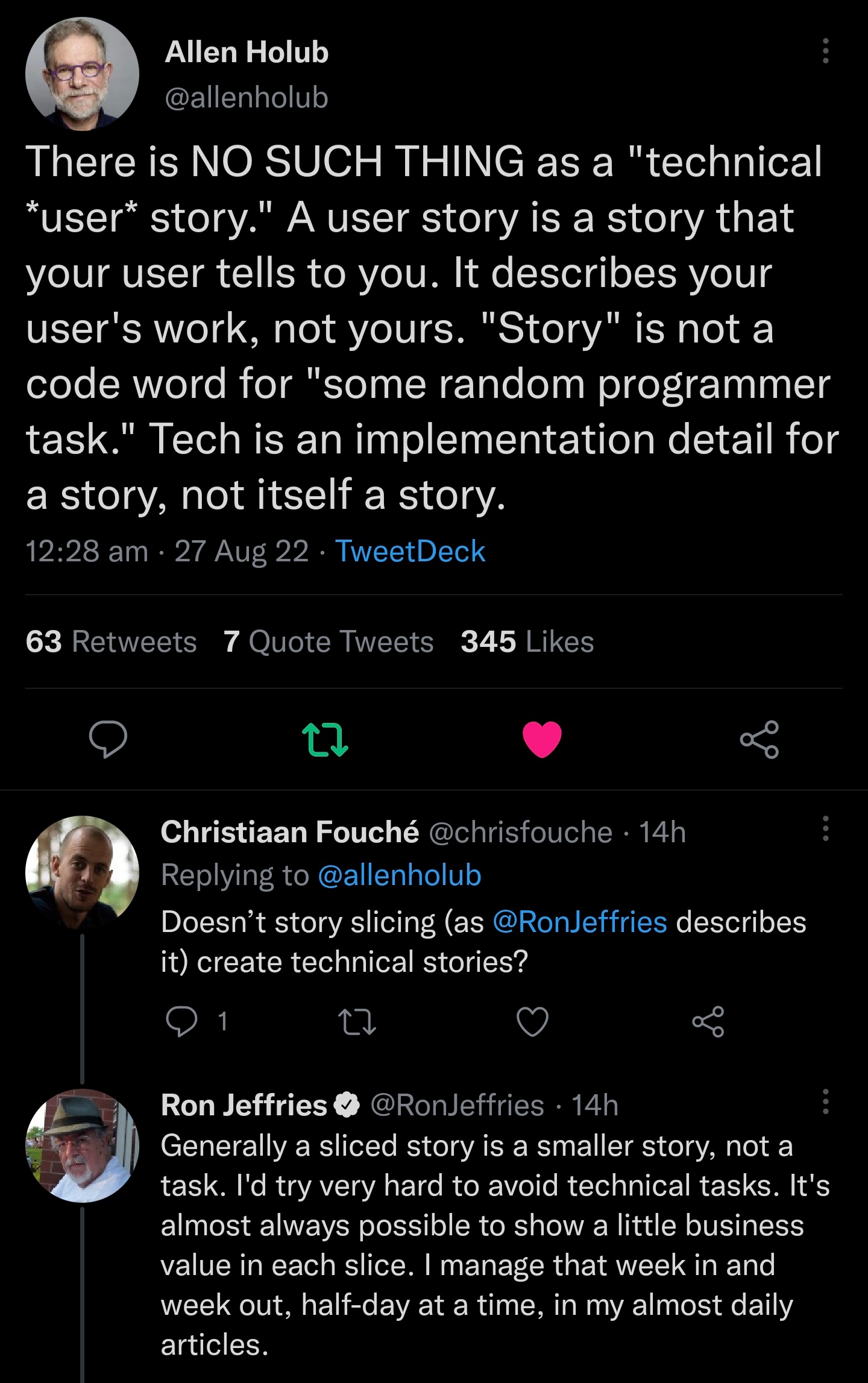

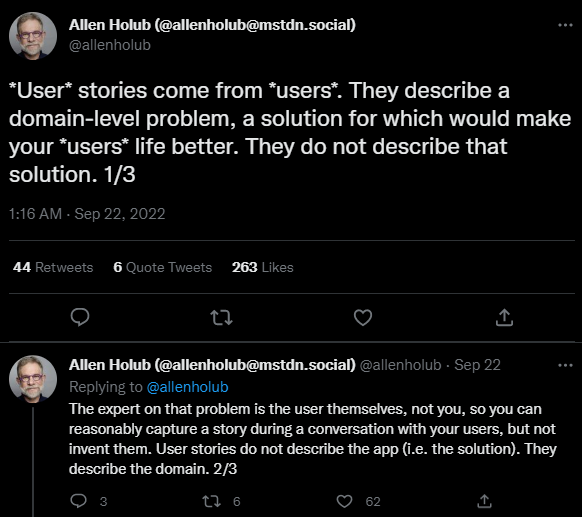

- We could not completely avoid stories that are only technical in nature, that are more often than not, sourced by engineering. Whether it’s refactoring, small configurations, or automations, there will be stories that are produced due to engineering necessity not directly related to business user stories/slices. In these cases, we generally prefix the story with [Dev] to denote that it is an isolated technical story - E.g. “[Dev] Remove unused function foo() of class bar, in order service business layer ” (This specific example is again oversimplified and may not need a story/task, but for the sake of demonstrating how we use this…)

On another note, the team also brainstormed and came up with a brilliant way of handling technical tasks (that could potentially impact existing architecture and system design) translated from highly complex business requirements. These type of requirements were not trivial to map out to story slices that could be addressed on their own. The solution was to map out individual story slices (and related technical/dev story slices) as nodes in a directed graph, stemming from root work items/nodes from which all other dependant nodes branch out (e.g. ‘implement feature flag for complex feature X’ would be a root work node for everything else that follows to implement feature X).

The directed edges of the graph specified dependencies (e.g. node A -> node B = work B cannot be started until work A is completed… There were some subtle cases where work B could be started even with work A partially completed, for which we created customized notation to represent this type of partial dependency). The entire graph was also overlaid with a lot of meta-data representing contexts of impacted systems, sub-system boundaries, interactions between components, and external actors/systems/services. The team would grow and evolve this map in cadence with iterative learning and discovery. This solution helped us avoid overlap/duplication between different pieces of work, as well as to discover missing stories/slices that were edge cases and/or hidden in the initial requirements (which were problems we initially had when we tried to do story slicing of highly complex requirements without having a visual aid/map/model, and tried to keep all the complexity in our heads). Now, we confidently move fast across the territory of complex changes required by the business.

Thinking on how we are evolving our planning and work breakdown in my team, I am reminded of some key highlights from Alistair Cockburn’s talk - Getting to the Heart of Agile (I highly recommend watching this talk), where he mentions that the world is always in a constant state of change, and to be agile, entails frequently probing the world and getting a feel for what is changing. The entire span of the value stream of a deliverable or a final end product is injected with thousands of decisions by hundreds of people within an organization. The final outcome is the embodiment of these hundred thousand or so decisions. Statistically, a person can make a mistake in one out of five (or ten) decisions they make. This could be compounded by people waiting on other people’s decisions to make their decisions, in a complex web of decision dependencies. This implies that we are shipping roughly ten thousand mistakes or bad decisions to production, wrapped within the artifacts and services that we deliver.

The engineering practices we adopt and follow should be geared towards shrinking the number of ‘decisions in process’ at a given time, and to discover better ways of probing the real world to get faster insight and feedback. Breaking down stories into story slices was one way we gained this, because for us smaller means better - easy to digest, simple to implement, and fast to validate. This helps us reduce the foot print of mistakes we make in our planning and work breakdown, as well as across the entire end-to-end value stream.